|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Fall 2010 Issue - Vol. 7, No.3

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Preview the Fall 2010 issue

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Writing assignment. That's right. We want readers to write an upcoming issue. It’s our special year-end Holiday Issue in which we invite readers to send in news about themselves and the land they care for in the form of a holiday greeting. Last year’s Holiday Issue, our first, was a big success. If you’re not yet a subscriber, this would be an especially good time to sign up. In a page or less, bring us up to date about you and your land, and we’ll publish your greeting to our family of readers just in time for the holidays. Send us a photo or two as well. Let’s make this year-end issue one big holiday card. .

---Mrs. Woods |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Here today, here tomorrow. “What’s to become of this fine prairie and savanna we’ve restored?” asks Alice D’Alessio in the leadoff story this issue. Hers is a concern shared by many landowners after the land passes to other owners. Perhaps you’re one of them. You’ll read how these concerns have fueled the growth of nonprofit groups known as land trusts. They’ve enabled landowners to attach to their deeds a legal device called a conservation easement. An easement can prevent future owners from doing things like building a house on the prairie they’ve restored. Alice’s story kicks off a series profiling landowners who have used conservation easements and other means to protect their work and the land in perpetuity. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| The caregivers. While anglers fish for trout in a nearby stream, Jim and Rose Sime cut burdock a few hundred yards away to save a sand prairie. Instead of fishing, this extraordinary couple enjoys nature by trying to save it---something they’ve done for years in the rugged driftless region of southwestern Wisconsin. In the mid-‘60s they began buying parcels of hilly, rocky land that local farmers didn’t think was worth much. But Jim and Rose found a wealth of rare plant species hidden in the weedy meadows and overgrown savannas. Their tireless efforts to save these remnant plant communities have given a shot in the arm to area conservation efforts. The Simes have taken out conservation easements to protect the land from the bulldozer, but they still worry about who’s going to fight the burdock and do the controlled burns after they’re gone. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| The visionary. “It’s time to give this farm back to Mother Nature,” says David Jacobson of the farm his grandfather homesteaded in 1885. So begins the story about Jacobson’s quest to restore a semblance of the oak savannas, woodlands, prairies and wetlands that confronted his Swedish immigrant grandfather more than 100 years ago. Jacobson’s vision honors both the land’s pre-settlement roots and its agricultural past. “I want to honor my family for their courage and contributions,” he says. “But the way I see it, they only borrowed the land for 100 years.” A conservation easement figures into Jacobson’s vision, but it doesn’t stop there. He has also set up a charitable trust that will manage the land for the public good after he’s gone. Jacobson wants the farm to become a learning center for conservation and ecological restoration. “I may be the last Jacobson to live on this land, but like my ancestors, I will leave my tracks,” he says. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Preview last year's Holiday Issue filled with season's greetings from readers and other stories! We invite readers to send in greetings for this year's issue.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

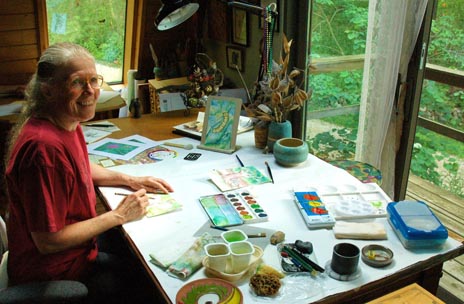

| Artist in residence. In the center spread this issue we feature a painting of prairie flowers by Judy Rogers. She once taught English at the college level, but art was always her first love. After marrying Dale Shriver (next story), a studio was a top priority when they remodeled the house in their 33-acre woodland near Marengo, Ill. She works in pastels, acrylics, pen-and-ink and charcoal, drawing inspiration from the natural world around her. “I hope my work and that of others will cause people to slow down and take a closer look at nature,” she says. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| The blue collar steward. McHenry County, Illinois, which includes some of Chicago’s northwestern suburbs, has lost 88 percent of its oak forests since 1837. In 1973 Dale Shriver happened to buy a piece of that forest, though at the time he didn’t know how important it was. He was an airplane mechanic who just wanted a place in the country, and so he bought this 33-acre parcel near Marengo. But Shriver was a quick learner and began to restore the woodland under the guidance of a DNR forester. He cleared underbrush, fought invasive species, and brought back the fires. He did the same with a 57-acre parcel he bought later, and was named tree farmer of the year for his efforts. That woodland is now protected by a conservation easement. In addition to work on his own land, Shriver joins other volunteers to work on public natural areas. The former airplane mechanic has become one of most dedicated defenders of the oaks of McHenry County. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| The Gift. Leonard Grimes and Mildred Hach grew up on farms a few miles from each other during the Great Depression. They married young and went on to professional careers---Leonard as an attorney, Mildred as an elementary school teacher. But they never forgot where they came from. In 1964 they bought a 160-acre farm on the west edge of Marshalltown, Ia. It is now the Grimes Farm Nature Center, a landmark environmental center and conservation showcase, managed by the Marshall County Conservation Board. Leonard and Mildred’s gift has served as a model for donating land to public agencies. Read how the Grimes’ transferred the land to Marshall County using a land trust as an intermediary. But this story goes beyond the ins and outs of donating land. It’s also about the love of two people for each other and for the land. The beautiful portrait of Leonard and Mildred was taken by Emily Grimes, a daughter-in-law. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| The yard lady. Meet Inger Lamb, our newest contributor. As the Yard Lady, Inger will be writing about the dos and don’ts of establishing prairies in smaller settings. In this issue she introduces her dog Maggie, who she uses to gauge proper heights of prairie plants in town. As the “Maggie-o-meter,” the dog warns against those tall prairie plants that flop over sidewalks and each other. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

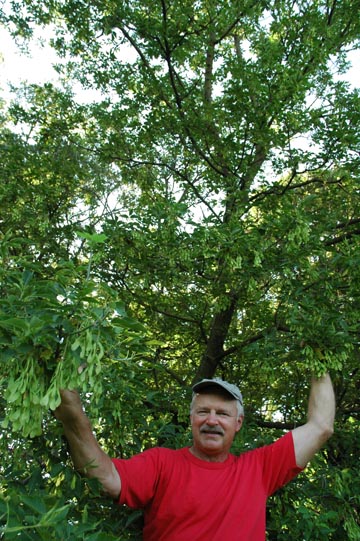

| The opportunists. Boxelder, prickly ash and gooseberry are natural born citizens of our woodlands. Yet these native plants are a nuisance when they stake out large areas of the understory and woodland edges as their own. In the photo to the left, Dan Bohlin, our Invasive Plants Guy, holds a boxelder that’s hogging space and preventing regeneration of oaks and black walnut. The goal is to control, but not eliminate wayward populations of these native plants. Dan tells how. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In other stories this issue:

The badger gets top billing on Wisconsin license plates purchased to support the state’s Endangered Resources Program. Little bluestem makes it big in Kansas as the official state grass. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Midwest Woodlands & Prairies is published four times a year by Wood River Communications.

© by Wood River Communications. Reproduction prohibited without written consent. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||